Category: Columns (Page 2 of 7)

Columns, arranged by topic, that I have written

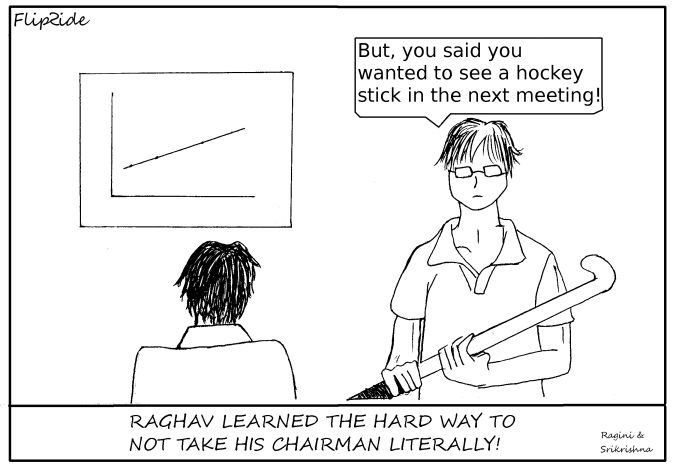

My daughter and I began doing a business cartoon back in 2011for the Hindu Business Line. Given father’s day I thought this might be a good one to share. I’ll try to share one each week.

Growing up, I recall my father gifting things to folks – in what I deemed – a reckless manner. There was time when someone admired my father’s wristwatch and he took it off and insisted that they take it. My sister and I argued with him, not just on that occasion but on several others that he was being taken advantage of. Of course his response was that there’s as much pleasure, maybe even more, in giving as there is in taking. My sister’s immediate offer of making him ecstatic by happily taking any and all gifts that he planned to give in the future, I don’t think was taken seriously.

Growing up, I recall my father gifting things to folks – in what I deemed – a reckless manner. There was time when someone admired my father’s wristwatch and he took it off and insisted that they take it. My sister and I argued with him, not just on that occasion but on several others that he was being taken advantage of. Of course his response was that there’s as much pleasure, maybe even more, in giving as there is in taking. My sister’s immediate offer of making him ecstatic by happily taking any and all gifts that he planned to give in the future, I don’t think was taken seriously.

Yet once I hit my teens, I became aware that whenever my father lent people money – particularly to a steady stream of strangers, often referred by relatives – for a family exigency or to buy a motorcycle or to go abroad to study, he always insisted that they sign a promissory note or pro-note as was called. This was usually a letter on plain paper, stating the amounts borrowed and the borrower’s intent to return the sums upon demand or by a certain date. The borrower signed it across a revenue stamp pasted on the paper, making it a legal contract. This was in marked contrast with how he handled grants at the small non-profit he ran, which usually gave money directly to elementary, middle or high schools for kids who needed financial help to pay their fees or for books. These grants were just that and the beneficiaries, usually economically disadvantaged kids, were not expected to pay the money back.

So I asked my dad, why he took pro notes from these other folks who borrowed money from him. His response was that if he didn’t treat the money as a loan, that he expected the borrower to return, it diminished the value perceived by the borrower. While most borrowers intended to return the money, it didn’t hurt that there was a legal reason for them to pay off the loan. As my dad put it, “If they return the money, it allows me to lend it to more people who could use a helping hand.”

Ronald Reagan is credited with popularizing the term “Trust but verify” (or as the Russian proverb went “doveryai, no proveryai”). This was my dad’s own method to keep himself and others honest.

“That is what TTN has visualized.” I’d heard my dad say this so many times as I was growing up. TTN was TT Narasimhan, his boss – who relied heavily on my dad as his execution guy. In later years, my father took on the role of the CEO of two group companies and was left to call the shots in these and other businesses. Yet, in almost all public instances, my dad never did anything without indicating that he was only carrying out TTN’s vision. While not comfortable himself with any form of public praise, he was never failed to point out the contribution of TTN, when someone praised or credited him with any success. Even in the hierarchy and sycophancy-laden culture of India in the 70s, it was clear that it was something else that drove my dad.

I recall, once having a big argument (at least that’s how it seemed to me) with my dad, as to why he did not take credit for a lot of what were clearly his own ideas and doing. My dad gave me the indulgent smile he was wont to, when he felt I was being particularly childish or unreasonable. “Son, keep in mind, that all I’m able to do is because of the freedom and trust, not to mention the capital that TTN has provided. It’s in his name that we are borrowing money – that enables us to do what we are doing.” He could see clearly that this did not cut much ice with me. “Even without all of that, there are two things to keep in mind son,” he continued. “It does take vision – not everyone can provide it. And giving credit to others does not take anything away from your own contribution.”

I can’t say that I was convinced that day. Several years later, when he had hired several PhDs in the research department of the pharmaceutical firm he was the CEO off, I saw this in action again. My dad had only graduated from high school, as his father’s death while he was still in 9th standard, and the family’s financial situation did not allow him to pursue a college degree. So here was a man, with no formal qualifications other than a high school diploma from a small town in Tamil Nadu, who’d worked his way up from accounting apprentice through chief accountant to eventually CEO of two firms. “All credit has to go to our scientists for how well our firm is doing today,” was his constant refrain.

At my father’s funeral last year, many strangers came up to me and said “I was able to pursue college or go overseas only because of your dad.” So my dad’s exhortation to “Spread the credit” clearly had not undermined him in any way – his actions spoke loud enough.

This is a lesson that I’ve finally begun to appreciate and practice. Let me tell you about all that things that I’ve learned from Rajagopal….

As with most sayings there’s a good deal of truth to the truism—history is written by the victors. And rarely do such histories dwell on the mistakes or, worse yet, atrocities committed by the victors. While modern historians have attempted people’s histories or stories of the subaltern, as academics are fond of calling it, it’s pretty certain most histories are not exactly balanced reporting.

Stories of entrepreneurial journeys in many ways are not that different from histories written by the victors. Many of them are only slightly better than hagiographic biographies written by adoring admirers. Baskar Subramanian, one of the co-founders of my first start-up is fond of pointing out that once an entrepreneur is successful, he can write the story of his journey in any manner he deems fit. So if a start-up saga contains few mistakes, almost no accidents or lucky breaks, and where every major decision was the result of great strategic thought, you know you are reading a history by the victor. So a bucket of salt may be required when you read such a history or seek to learn from it.

Even when an entrepreneur is clearly successful and well thought of on matters of integrity, such as Sam Walton, the founder of Wal-Mart, or for someone closer to home, J.R.D. Tata, the matter of relevance, particularly to a fledgling start-up, becomes important. A reader is at best able to draw only general lessons about perseverance or passion. India and the world are a significantly different place today than when these men built their businesses. So, how practical are their insights for an entrepreneur to apply today? Inspiration is critical and these tomes offer them, certainly, but entrepreneurs need more than inspiration. They need practical and proven insights that can be both internalized and implemented with ease. Do books of even recent entrepreneurial success, pertain only to a market segment—modern retail or generic drugs—or can their lessons be applied to any entrepreneur starting up?

With the advent of blogs, particularly those professing advice for entrepreneurs, a number of interview series, and subsequently, books of interviews of entrepreneurs have emerged. These overcome the shortcomings of a single subject or company book and are often stories of recent or still-running businesses, which the readers not only relate to but also are likely to encounter in their lives. Yet, not each of these are written (or worse yet edited) in a manner that makes them as palatable and useful as one would like.

The first challenge when trying to learn from the lessons of others is figuring out which lessons are relevant to your own situation. Once you identify the problems that are similar, if not identical, to your own, you’d have to figure out whether the solution is germane to your own situation. Hiring for a software product start-up may be just as difficult in Bangalore as it is in Mountain View or New York—however, the solution may be altogether different.

Founders at Work: Stories of Startups’ Early Days by Jessica Livingston stands head and shoulders above most other compilations of founder stories. While largely confined to Silicon Valley founders (whose origins are as varied as Brazil, China, India and Russia—and more interestingly the lesser-heralded towns of US states such as Nebraska and Iowa) and what would be termed as “tech” start-ups in India, many of the lessons are broadly applicable to start-ups anywhere.

The 32 stories in Founders at Work are set in Q&A form, with mercifully short questions. The entrepreneurs’ answers are delivered in direct and often in an unflatteringly candid manner. The book, which I’d avoided reading for a long time, gripped me from the first page. The book works because it keeps its focus on the earliest days of the start-ups—whether they subsequently grew into today’s Apple or self-destructed like ArsDigita or were acquired like Hotmail or TripAdvisor. This is one book of start-up stories that you cannot do without, even if you never intend to start something on your own. You’ll do better at your job as will your company if you read this book and take its lessons to heart.

This last week I made a mistake for a second time and paid for it dearly. A friend had offered to book a hotel for me and feeling lazier than usual I’d agreed. And when she sent me an email with the reservation I actually felt good, because she’d booked me in a fancy downtown hotel at bargain rates. Of course, only when I showed up at the registration desk did I realize that I’d confused my drachmas for dirhams. So the good deal in a downtown hotel, for what I thought was $100 a night, turned out to be nearly $400. But by then it was too late not just with the non-refundable booking but also on a long day after a long flight with the family in tow. I reckoned might as well have a good time. But I was in for yet another shock. The lady behind the desk had a most snarky attitude. “No! Breakfast is not included with your room. It is $30 per person.” “No, there’s no free wi-fi—$7 for an hour or $15 for a day. By the way that’s per device.”

None of this rankled as much as her attitude that she clearly didn’t care how I felt and she absolutely felt no need to be even remotely polite. In contrast, the hotels that I’d stayed at the night before and the two nights afterwards, each cost well below $100 per night and offered free breakfast and free wi-fi (in only the lobby in one case and all over the hotel in the other). More importantly, both had extremely friendly folks at the front desk—who were happy to let us check in early, check out late and went out of their way to help us have a good time. And these were employees, who certainly were paid a whole lot less than my snarky host at the $400 a night hotel. My little one asked in the puzzled tone she uses when she doesn’t understand something, “Why did that lady have such a bad attitude dad?” And, of course, answered herself quickly, “Maybe she had a fight with her boyfriend!” What was evident to my 13-year-old was clearly not evident to the owners of this fancy hotel —not the boyfriend part but the fact that attitude matters. This lady with her snarky attitude did not only prevent us from enjoying our stay at $400 a night but made sure that we’d not go back there.

“I can’t just get them to take ownership.” How many times have we heard this refrain from managers or entrepreneurs? And how often have we voiced this sentiment ourselves? It seems like we all run into folks who can’t look at what they do to be anything more than a job. Something they do to make a living—put food on the table, pay the bills—and they can’t wait for 5 o’clock or the end of their shift, so that they can get back to their real lives. Sure we may use other words or expressions—“Doesn’t he have any pride in what he does?” and “I can’t seem to make them care about the company or customers.”

In his book, A Stake in the Outcome, Jack Stack, CEO of SRC Holdings Corp., talks about building a culture of ownership among the people who run a business and the critical role it plays in the long-term success of a business. The book builds on his own experience of taking the original Springfield ReManufacturing Corp. where he was a manager, from the verge of failure to a major financial success. The original $0.10 stock in 1983 when Jack and his 12 manager colleagues took over the business was worth $81.60 in 2001—for a return of 816,000% in 18 years! But that’s not the story. It is how all 727 employees own shares—not just some shares, the 722 newest shareholders own 64% of the business valued at $23 million in 2002. I’d run out and get this book for everyone on your team to not just learn how Jack and has team achieved this but to repeat it with your business.

Waiters at French restaurants— maybe only at upscale French restaurants in the US—have a legendary reputation as unfriendly and at times downright disdainful. Of course, waiters across the social spectrum in India could easily teach their French cousins a thing or two about treating customers shoddily. And these are folks in the service business, where how you treat the customer is supposed to affect your business directly. Yet each of us can easily recount horror tales of poor customer service—be it with airlines, banks, call centres, retail outlets or telecom services—in practically every sphere of our personal lives. To be fair, customer service in India has come a long way since the early days of liberalization. The sheer choice of suppliers and healthy competition in the marketplace has done wonders to improve the manners of most frontline employees of service providers.

However, old habits die hard. A recent popular advertisement for a mobile service provider features a cantankerous old man who is bent upon ignoring, irritating or ill-treating his customers. And, as the Indian economy slows, the impact on businesses shows up first in the fraying edges of their customer interface. India is by no means alone in the decline. From the time of the Roman markets to the gleaming retail outlets of a resurgent Asia and gloomy malls of North America, customer service—good, consistent, delightful—has been a challenge.

Growing up in Chennai, I recall that nearly any retail store I went to had a small sign with a quote from Mahatma Gandhi. “A customer is the most important visitor on our premises. He is doing us a favour by giving us an opportunity to do so.” As with many other signs that dot the Indian landscape, such as No Entry—One Way Street or Do Not Spit or Cause Nuisance, Gandhi’s exhortation is “more honour’d in the breach than the observance”.

The service mindset has to begin at home. Indians, much like the Chinese and Japanese, like to pride themselves on being respectful to their elders. However, from our daytime soaps on TV to our overcrowded roads, thoughtlessness and rudeness, particularly towards elders, seems the rule. This behaviour just as easily spills into our malls and stores. If you’ve ever seen a parent admonish or worse yet slap their child at the supermarket, doesn’t it make you wonder how much worse they’d treat that child at home? Similarly, when you receive poor service from any professional service provider, you wonder—if this is how they treat their customers, how badly must they treat their employees?

Again, we needn’t wonder too long. Managers, at supermarkets certainly or even banks, don’t hesitate to dress down their employees right in front of the public. Many large Indian businesses, even when publicly listed, are often run as though they are proprietary firms where employee empowerment is largely absent. Multinational firms have succumbed to an Indian version of the Borgia families where politics and intrigue take much more of a manager’s time than advancing the business cause. However, as with every challenge that we face in India—and they are not only innumerable but often large—this itself presents an opportunity. An opportunity to provide exceptional service—to delight customers, differentiate a business and thereby thrive even in these difficult times.

The secret to achieve such exceptional service forms the very core of Hal Rosenbluth’s The Customer Comes Second. Co-authored with Diane McFerrin Peters, who works with Rosenbluth’s eponymous travel firm. His formula for creating an organization that provides exceptional service is to put your employees first and your customers second. Before we dismiss this as simplistic, it’s worth noting that Rosenbluth Travel has clocked more than $6 billion in annual revenue and has better than 98% customer retention. So clearly they must be doing something right. For the hard-nosed, what-can-I-actionize reader, the book offers specific tips and tools starting from finding the right people and training them all the way to using technology. Any book that talks unabashedly about culture and happiness in the workplace as this one does is a keeper and you should steal it from your nearest library.

This article originally appeared in the Book Beginnings column in Mint.

There are few things that have been written so much about and yet not understood well as leadership – okay possibly parenting, but that’s for another place and day. Stop the next six people you encounter today and ask them about their favorite leader and what it is that makes them a great leader. You are likely to get at last six different answers, possibly more. If we dig a little deeper we’ll also discover people expect different things from different leaders – as in what constitutes a great statesman, a successful business leader, a politician or a community or social leader. Whilst all this is natural and not unexpected, it is of little help for those of us looking to role models and to answer the question how do I become a leader and what should I do as a leader.

There is the common perception, quite widely held even in business circles, of an awe-inspiring, charismatic leader – gimlet eyed, firm jawed capable of making rapid decisions – sort of Churchill sans the cigar. Jack Welch of General Electric and Henry Nicholas, former CEO of Broadcom fall into this category of leader models. At the other extreme we have Bill Gates one of the most successful entrepreneurs of all time, who till a few years back was underwhelming at best in his public presentations. Yet the leaders we meet everyday – even the few that we admire seem to be cut from as many different types of cloth as there are men and women.

Closer home, few Indian business leaders have gotten the same measure of public exposure or attention that Bollywood, cricket or politics gets, for us to easily draw definitive stands on leadership styles. Politics by virtue of its very nature, throws up a large share of leaders, at least ones that get a disproportionate share of air time. Interestingly Indian politics, especially recently, has thrown up a wide and varied share of leaders – particularly women leaders – J. Jayalalitha, Mamta Bannerjee, Mayawati and of course Sonia Gandhi. Fewer groups could be as dissimilar as these four women and yet they command respect with vast swathes of people and wield considerable power. Their styles are as varied as the regions the cuisines of India are. Similarly, for the first time since Independence, men and women such as Aruna Irani, Kiran Bedi and Anna Hazare, who are not politicians, movie stars or cricketers have captured our attention and imagination. Their use of social and new media in combination with old style street activism, itself offers some interesting lessons in both leading change and leadership styles.

The challenge of course in formulating our leadership lessons from politicians and business leaders, whether in India or overseas, particularly from what is written about them is in separating the myth from reality. The natural question is that how much of this is business, culture or country specific and should we look to Indian business leaders to draw lessons for ourselves? Unfortunately a good deal of writing about business leaders in India has been panegyric limiting their usefulness as lessons in leadership. Fortunately much of what has been written about business leaders overseas, even when not scholarly, has been done so in mostly an objective manner and occasionally in an outright critical manner.

Warren Bennis’ “On Becoming a Leader” was inspired in his own words “by the gap between theory and practice, the difference between what one thinks and teaches and what one does.” By covering 28 specific individuals – men and women, all American, across a variety of professions, helps identify the critical ingredients for leadership success. More importantly he outlines a way to grow those qualities in us and in the people we will lead. As he states up front in his introduction, in his first book “Leaders” he covered the “Whats” and in this book, he covers the “Hows.” In the mold of Tom Peters and Peter Drucker, Warren Bennis has carved himself a seminal role in business through his research on Leadership. This book of his, rooted as it is in the real world of practicing leaders can help each of us become the leader we are fully capable of being.

This article originally appeared in the Book Beginnings column in Mint.

You must be logged in to post a comment.